Syllabus: PPOL 6801 - Text as Data: Computational Linguistics

Data Science and Public Policy, McCourt School for Public Polcy, Georgetown University

Course Description

In recent years, the surge in the availability of textual data, ranging from the digitalization of archival documents, political speeches, social media posts, and online news articles, has led to a growing demand for statistical analysis using large volumes of text data. In this course, we will teach students how to analyze and somewhat collect this data from a social science viewpoint. The focus is on understanding the real-world use of text as data rather than just the theory behind it. Students will learn how to acquire text, turn text into data, and analyze it to answer important policy-relevant questions. Each week, we’ll go over different methods, like building and using dictionaries, understanding sentiment in text, scaling texts on ideological and policy dimensions, and using machine learning to classify text. Lectures will include hands-on activities, letting students work directly with actual texts, and I strongly encourage students to bring their own data to class. The course aims to equip students with a variety of text analysis techniques that will be valuable for their future work as policy experts and computational social scientists.

While the course covers an interdisciplinary topic, and many of the techniques we discuss have their origins in computer science or statistics, we will spend relatively little time on traditional Natural Language Processing techniques, such as machine translation, optical character recognition, and parts of speech tagging, etc. Although we will touch on Large Language Models (ChatGPT) at the end of the course, we will focus mostly on the practical use of these models through their APIs instead of building up and providing an in-depth understanding of their architecture.

I assume students taking this class have taken, at minimum, an introductory class in statistics and have basic knowledge of probability, distributions, hypothesis testing, and linear models. The core language and software environment of this course is R. If you are not familiar with R, you will struggle with the assigned exercises. We will also provide some code in Python, but no prior knowledge here is assumed since this will be additional material.

Instructor

- Pronouns: He/Him

- Email: tv186@georgetown.edu

- Office hours: Every Tuesday, 4pm - 6pm

- Location: Old north, 312

Our classes

Classes will take place at the scheduled class time/place and will involve a combination of lectures, coding walkthrough, breakout group sessions, and questions. We will start our classes with a lecture highlighting what I consider to be the broader substantive and programming concepts covered in the class. From that, we will switch to a mix of coding walk through and breakout group sessions.

This class follows a more classic PhD style seminar. This means that the class is heavy on the readings, and I expect you to do the readings before class. For most classes, you will read one or more chapters of the text book and between two or three applied articles. Most of the lectures will cover topics discussed on the readings.

Note that this class is scheduled to meet weekly for 2.5 hours. I will do my best to make our meetings dynamic and enjoyable for all parts involved. We will take one or two breaks in each of our lecture.

Required Materials

Readings: We will rely primarily on the following textbooks for this course. While this textbook is not freely available online, all the other materials of the course will be or should be accessible through Georgetown library.

Grimmer, Justin, Margaret E. Roberts, and Brandon M. Stewart. Text as data: A new framework for machine learning and the social sciences. Princeton University Press, 2022 - [GMB]

Daniel Jurafsky and James H. Martin. Speech and Language Processing, 3nd Edition. - [SLP]

The weekly articles are listed in the syllabus

Course Infrastructure

Class Website: A class website will be used throughout the course and should be checked on a regular basis for lecture materials and required readings.

Class Slack Channel: The class also has a dedicated slack channel. The channel serves as an open forum to discuss, collaborate, pose problems/questions, and offer solutions. Students are encouraged to pose any questions they have there as this will provide the professor and TA the means of answering the question so that all can see the response. If you’re unfamiliar with, please consult the following start-up tutorial (https://get.slack.help/hc/en-us/articles/218080037-Getting-started-for-new-members).

Canvas: A Canvas site (http://canvas.georgetown.edu) will be used throughout the course and should be checked on a regular basis for announcements and assignments. All announcements for the assignments and classes will be posted on Canvas; they will not be distributed in class or by e-mail. Support for Canvas is available at (202) 687-4949

Weekly Schedule & Readings

Week 1: Introduction - Overview of the course

Topics: Review of syllabus and class organization. Introduction to computational text analysis.

- [GMB] - Chapter 2.

Or one of the three below:

Political Science Perspective: Wilkerson, J. and Casas, A. (2017). Large-Scale Computerized Text Analysis in Political Science: Opportunities and Challenges. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 529:544.

Economics Perspective: Gentzkow, Matthew, Bryan Kelly, and Matt Taddy. “Text as data.” Journal of Economic Literature 57, no. 3 (2019): 535-574.

Sociology Perspective: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049089X22000904

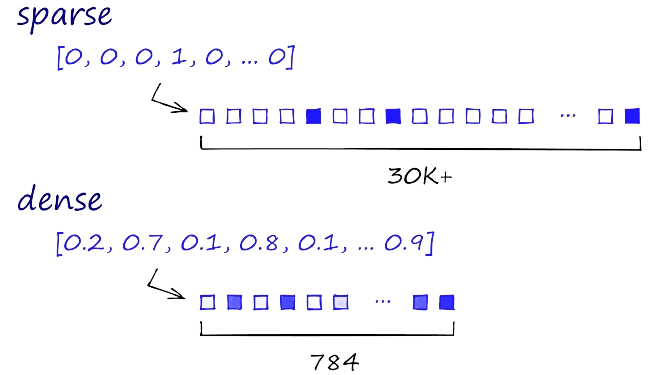

Week 2: From Text to Matrices: Representing Text as Data

Topics: How to represent text as data? What is a Bag of Words? What are tokens? Why should we care about tokens?

-[GMB] - Chapters 3-5

Applied Papers:

Denny, M. J., & Spirling, A. (2018). Text preprocessing for unsupervised learning: why it matters, when it misleads, and what to do about it. Political Analysis, 26(2): 168-189.

Ban, Pamela, Alexander Fouirnaies, Andrew B. Hall, and James M. Snyder. “How newspapers reveal political power.” Political Science Research and Methods 7, no. 4 (2019): 661-678.

Michel, J.B., et al. 2011. “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books.” Science 331 (6014): 176–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199644;

Week 3: Text Similarity, Text re-use and Complexity

Topics: How do we evaluate complexity in text? Why should we care about complexity in text? How do we evaluate similarity in text? Why is this useful?

[GMB] - Chapter 7

Applied Papers:

Spirling, Arthur. 2016. “Democratization and Linguistic Complexity”, Journal of Politics.

Benoit, K., Munger, K. and Spirling, A. 2017. Measuring and Explaining Political Sophistication Through Textual Complexity

Linder, Fridolin, Bruce Desmarais, Matthew Burgess, and Eugenia Giraudy. “Text as policy: Measuring policy similarity through bill text reuse.” Policy Studies Journal 48, no. 2 (2020): 546-574.

Week 4: Supervised Learning I: Dictionary Methods and Out of Box Classifier Analysis

Topics: What are dictionaries? Why/when are they useful? What are their limitations? Can we use models trained by others?

[GMB] - Chapters 15-16

Applied Papers:

Lori Young and Stuart Soroka 2012 “Affective News: The Automated Coding of Sentiment in Political Texts.” Political Communication, 29:2, 205-231.

Rathje, Steve, Jay J. Van Bavel, and Sander Van Der Linden. “Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 26 (2021): e2024292118.

Ventura, Tiago, Kevin Munger, Katherine McCabe, and Keng-Chi Chang. “Connective effervescence and streaming chat during political debates.” Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 1 (2021).

Problem set 1 Assigned

Week 5: Supervised Learning II: Training your own classifiers

Topics: We will study the framework to train our own supervised models, and when to use them.

[GMB] - Chapters 17, 18, 19, and 20.

Applied Papers:

Barberá, Pablo, Amber E. Boydstun, Suzanna Linn, Ryan McMahon, and Jonathan Nagler. “Automated text classification of news articles: A practical guide.” Political Analysis 29, no. 1 (2021): 19-42.

Siegel, Alexandra, et al. “Trumping Hate on Twitter? Online Hate Speech in the 2016 US Election Campaign and its Aftermath.”

Theocharis, Y., Barberá, P., Fazekas, Z., & Popa, S. A. (2020). The dynamics of political incivility on Twitter. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020919447.

Mitts, T., Phillips, G., & Walter, B. (2021). Studying the Impact of ISIS Propaganda Campaigns. Journal of Politics

Week 6: Replication Class I: Students’ Presentation

Week 7: Unsupervised Learning: Topic Models

Topics: what if we do not have an outcome to predict? can we cluster the text in groups? what are topics?

[GMB] - Chapters 12-14.

David M. Blei . 2012. “Probabilistic Topic Models.” http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~blei/papers/ Blei2012.pdf

Applied Papers:

Motolinia, Lucia. Electoral accountability and particularistic legislation: evidence from an electoral reform in Mexico. American Political Science Review 115, no. 1 (2021): 97-113.

Barberá, P., Casas, A., Nagler, J., Egan, P. J., Bonneau, R., Jost, J. T., & Tucker, J. A. (2019). Who leads? Who follows? Measuring issue attention and agenda setting by legislators and the mass public using social media data. American Political Science Review, 113(4), 883-901.

Eshima, Shusei, Kosuke Imai, and Tomoya Sasaki. “Keyword‐Assisted Topic Models.” American Journal of Political Science (2020).

Week 8: Word Embeddings: What they are and how to estimate?

Topics: What are word-embeddings? When and how can we use them? What? Topic models again? Is this still a bag of words?

[GMB] - Chapter 8.

[SLP] Chapter 6, “Vector Semantics and Embeddings.”

Spirling and Rodriguez, Word embeddings: What works, what doesn’t, and how to tell the difference for applied research.

Week 10: Using Text to Measure Ideology - Scaling

Topics: What are scaling models and what can they tell us? Can we represent politicians/users ideology using text?

Applied Papers:

Laver, Michael, Kenneth Benoit, and John Garry. 2003. “Extracting Policy Positions from Political Texts Using Words as Data”. American Political Science Review. 97, 2, 311-331

Slapin, Jonathan and Sven-Oliver Prokschk. 2008. “A Scaling Model for Estimating Time-Series Party Positions from Texts.” American Journal of Political Science. 52, 3 705-722

Rheault, Ludovic, and Christopher Cochrane. “Word embeddings for the analysis of ideological placement in parliamentary corpora.” Political Analysis 28, no. 1 (2020): 112-133.

Aruguete, Natalia, Ernesto Calvo, and Tiago Ventura. “News by popular demand: Ideological congruence, issue salience, and media reputation in news sharing.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 28, no. 3 (2023): 558-579.

Izumi, Mauricio Y., and Danilo B. Medeiros. “Government and opposition in legislative speechmaking: using text-as-data to estimate Brazilian political parties’ policy positions.” Latin American Politics and Society 63, no. 1 (2021): 145-164.

Week 11: Replication Class II: Students’ Presentation

Week 12: Large Language Models: Theory and Fine-tuning a Transformers-based model (Inviter Speaker: Dr. Sebastian Vallejo)

Topics: We will learn about the Transformers architecture, attention, and the encoder-coder infrastructure.

[SLP] - Chapter 10.

Jay Alammar. 2018. “The Illustrated Transformer.” https://jalammar.github.io/illustratedtransformer/

Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30;

Timoneda and Vera, BERT, RoBERTa or DeBERTa? Comparing Performance Across Transformer Models in Political Science Text, Forthcoming Journal of Politics.

Week 13: Large Language Models: Outsourcing Applications

Applied Papers: We will see some social science application of LLMs chatbots. Can we use ChatGPT to perform zero-shot classification tasks? What are the concerns of these applications?

Week 14: Final Projects: Students Presentation

Course Requirements

| Assignment | Percentage of Grade |

|---|---|

| Participation/Attendance | 10% |

| Problem Sets | 20% |

| Replication Exercises | 30% |

| Final Project | 40% |

Participation and Attendance (10%):

Data science is an cooperative endeavor, and it’s crucial to view your fellow classmates as valuable assets rather than rivals. Your performance in the following aspects will be considered when assessing this part of your grade:

Active involvement during class sessions, fostering a dynamic learning environment.

Contributions made to your group’s ultimate project.

Assisting classmates by addressing problem set queries through GitHub issues. Supporting your peers will enhance your evaluation in terms of teamwork and engagement

Assisting classmates with slack questions, sharing interesting materials on slack, asking question, and anything that provides healthy contributtions to the course.

Problem Sets (20%):

You will have a week to complete your assignments

Students will be assigned three problem sets over the course of the semesters. While you are encouraged to discuss the problem sets with your peers and/or consult online resources, the finished product must be your own work. The goal of the assignment is to reinforce the student’s comprehension of the materials covered in each section.

The problems sets will assess your ability to apply the concepts to data that is substantially messier, and problems that are substantially more difficult, than the ones in the coding discussion in class.

I will distribute the assignment through a mix of canvas and github. The assignments can be in the form of a Jupyter Notebook (.ipynb) or Quarto (.qmd). Students must submit completed assignments as a rendered .html file and the corresponding source code (.ipynb or .qmd).

The assignments will be graded in accuracy and quality of the programming style. For instance, our grading team will be looking at:

- all code must run;

- solutions should be readable

- Code should be thoroughly commented (the Professor/TA should be able to understand the codes purpose by reading the comment),

- Coding solutions should be broken up into individual code chunks in Jupyter/R Markdown notebooks, not clumped together into one large code chunk (See examples in class or reach out to the TA/Professor if this is unclear),

- Each student defined function must contain a doc string explaining what the function does, each input argument, and what the function returns;

- Commentary, responses, and/or solutions should all be written in Markdown and explain sufficiently the outpus.

- All solutions must be completed in Python.

The follow schedule lays out when each assignment will be assigned.

| Assignment | Date Assigned | Date Due |

|---|---|---|

| No. 1 | Week 4 | Before EOD of Week 5’s class |

| No. 3 | Week 9 | Before EOD of Week 10’s class |

Replication Exercises (30%)

Replication exercises are adapted from Gary King’s work here and here. Replication consists in the process of repeating a research study using the original data or brining new data to the conversation. Replicability is crucial for the advancement of knowledge and the credibility of scientific inquiry.

For our purposes, replication exercises will work as a educational tool. A common say in science is that you just learn a new skill/methods when you use in your own work. Since we do not have time to write three papers during a semester, we will take advantage of published work with open available datasets and code for us to work on replication exercises.

You will work in pairs for this assignment. Your partner will be randomly assigned. You will repeat this exercise twice throughout the course. This is a stylized step-by-step of this exercise:

Step 1: finding a paper to replicate

- By the end of the week 2 and week 7, you should select an article from the syllabus to be replicated by you.

- The first replication exercise should consider articles from weeks 2 to week 5, and the second from the remaining of the class.

Step 2: Acquiring the Data

- Most research articles are published with open data rules. This means their data and code are often available on github, or on harvard dataverse. Your first task is to find the data and code from these articles.

- If your articles does not have the data and code, you should:

- Politely contact the authors of the article and ask for the replication materials

- If you don’t get response, select another article.

Step 3: Presentation

- For weeks 6 and 11, you will do a presentation of your replication efforts.

- The presentation should have the following sections:

- Introduction: introduction summarizing the article.

- Methods: data used in the article

- Results: the results you were able to replicate

- Differences: any differences between your results and the authors’

- Autopsy of the replication: what worked and what did not work

- Extension: what would you do different if you were to write this article today? Where would you innovate?

Step 4: Replication Repository

- By Friday EOD of each replication week, you should share with me and all your colleagues your replication report. The replication report should be:

- a github repo with a well-detailed readme. See an model here: https://github.com/TiagoVentura/winning_plosone

- your presentation as a pdf

- the code used in the replication as a notebook (Markdown or Jupyter)

- a report with maximum of 5 pages (it is fine if you do less than that) summarizing the replication process, with emphasis on three sections of your presentation: Differences, Autopsy and Extension.

- By Friday EOD of each replication week, you should share with me and all your colleagues your replication report. The replication report should be:

In addition to following the requirements above, the replication exercises will also be graded in accuracy and quality of the programming style. For instance, our grading team will be looking at:

- all code must run;

- solutions should be readable

- Code should be thoroughly commented (the Professor/TA should be able to understand the codes purpose by reading the comment),

- Coding solutions should be broken up into individual code chunks in Jupyter/R Markdown notebooks, not clumped together into one large code chunk (See examples in class or reach out to the TA/Professor if this is unclear),

- Each student defined function must contain a doc string explaining what the function does, each input argument, and what the function returns;

- Commentary, responses, and/or solutions should all be written in Markdown and explain sufficiently the outpus.

Final Project (40%): Data science is an applied field and the DSPP is particularly geared towards providing students the tools to make policy and substantive contributtions using data and recent computational developments. In this sense, it is fundamental that you understand how to conduct a complete analysis from collecting data, to cleaning and analyzing it, to presenting your findings. For this reason, a considerable part of your grade will come from a an independent data science project, applying concepts learned throughout the course.

The project is composed of three parts:

- a 2 page project proposal: (which should be discussed and approved by me)

- an in-class presentation,

- A 10-page project report.

Due dates and breakdowns for the project are as follows:

| Requirement | Due | Length | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project Proposal | EOD Friday Week 9 | 2 pages | 5% |

| Presentation | Week 14 | 10-15 minutes | 10% |

| Project Report | Wednesday Week 15 | 10 pages | 25% |

Important notes about the final project

For the project proposal, you need to schedule a 30min with me at least a week before the due date. For this meeting, I expect you to send me a draft of your ideas.

For the presentation, You will have 10-15 minutes in our last class of the semester to present you project.

Take the final project seriously. After you finish your Masters, in any path you take, you will need to show concrete examples of your portfolio. This is a good opportunity to start building it.

Your groups will be randomly assigned.

Submission of the Final Project

The end product should be a github repository that contains:

The raw source data you used for the project. If the data is too large for GitHub, talk with me, and we will find a solution

Your proposal

A README for the repository that, for each file, describes in detail:

Inputs to the file: e.g., raw data; a file containing credentials needed to access an API

What the file does: describe major transformations.

Output: if the file produces any outputs (e.g., a cleaned dataset; a figure or graph).

A set of code files that transform that data into a form usable to answer the question you have posed in your descriptive research proposal.

Your final 10 pages report (I will share a template later in the semester)

Of course, no commits after the due date will be considered in the assessment.

Grading

Course grades will be determined according to the following scale:

| Letter | Range |

|---|---|

| A | 95% – 100% |

| A- | 91% – 94% |

| B+ | 87% – 90% |

| B | 84% – 86% |

| B- | 80% – 83% |

| C | 70% – 79% |

| F | < 70% |

Grades may be curved if there are no students receiving A’s on the non-curved grading scale.

Late problem sets will be penalized a letter grade per day.

Communication

Class-relevant and/or coding-related questions,

Slackis the preferred method of communication. Please use the general or the relevant channel for these questions.For private questions concerning the class, email is the preferred method of communication. All email messages must originate from your Georgetown University email account(s). Please email the professor directly rather than through the Canvas messaging system.

I will try my best to respond to all emails/slack questions within 24 hours of being sent during a weekday. I will not respond to emails/slack sent late Friday (after 5:00 pm) or during the weekend until Monday (9:00 am). Please plan accordingly if you have questions regarding current or upcoming assignments.

Only reach out to the professor or teaching assistant regarding a technical question, error, or issue after you made a good faith effort to debugging/isolate your problem prior to reaching out. Learning how to search for help online is a important skill for data scientists.

Electronic Devices

When meeting in-person: the use of laptops, tablets, or other mobile devices is permitted only for class-related work. Audio and video recording is not allowed unless prior approval is given by the professor. Please mute all electronic devices during class.

Georgetown Policies

Disability

If you believe you have a disability, then you should contact the Academic Resource Center (arc@georgetown.edu) for further information. The Center is located in the Leavey Center, Suite 335 (202-687-8354). The Academic Resource Center is the campus office responsible for reviewing documentation provided by students with disabilities and for determining reasonable accommodations in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ASA) and University policies. For more information, go to http://academicsupport.georgetown.edu/disability/

Important Academic Policies and Academic Integrity

McCourt School students are expected to uphold the academic policies set forth by Georgetown University and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Students should therefore familiarize themselves with all the rules, regulations, and procedures relevant to their pursuit of a Graduate School degree. The policies are located at: http://grad.georgetown.edu/academics/policies/

Applied to this course, while I encourage collaboration on assignments and use of resources like StackOverflow, the problem sets will ask you to list who you worked on the problem set with and cite StackOverflow if it is the direct source of a code snippet.

ChatGPT

In the last year, the world was inundated with popularization of Large Language Models, particularly the easy use of ChatGPT. I see ChatGPT as Google on steroids, so I assume ChatGPT will be part of your daily work in this course, and it is part of my work as a researcher.

That being said, ChatGPT does not replace your training as a data scientist. If you are using ChatGPT instead of learning, I consider you are cheating in the course. And most importantly, you are wasting your time and resources. So that’s our policy for using LLMs models in class:

Do not copy the responses from chatgpt – a lot of them are wrong or will just not run on your computer.

Use chatgpt as a auxiliary source.

If your entire homework comes straight from chatgpt, I will consider it plagiarism.

If you use chatgpt, I ask you to mention on your code how chatgpt worked for you.

Statement on Sexual Misconduct

Georgetown University and its faculty are committed to supporting survivors and those impacted by sexual misconduct, which includes sexual assault, sexual harassment, relationship violence, and stalking. Georgetown requires faculty members, unless otherwise designated as confidential, to report all disclosures of sexual misconduct to the University Title IX Coordinator or a Deputy Title IX Coordinator. If you disclose an incident of sexual misconduct to a professor in or outside of the classroom (with the exception of disclosures in papers), that faculty member must report the incident to the Title IX Coordinator, or Deputy Title IX Coordinator. The coordinator will, in turn, reach out to the student to provide support, resources, and the option to meet. [Please note that the student is not required to meet with the Title IX coordinator.]. More information about reporting options and resources can be found on the Sexual Misconduct

Website: https://sexualassault.georgetown.edu/resourcecenter

If you would prefer to speak to someone confidentially, Georgetown has a number of fully confidential professional resources that can provide support and assistance. These resources include: Health Education Services for Sexual Assault Response and Prevention: confidential email: sarp[at]georgetown.edu

Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS): 202.687.6985 or after hours, call (833) 960-3006 to reach Fonemed, a telehealth service; individuals may ask for the on-call CAPS clinician

More information about reporting options and resources can be found on the Sexual Misconduct Website.

Provost’s Policy on Religious Observances

Georgetown University promotes respect for all religions. Any student who is unable to attend classes or to participate in any examination, presentation, or assignment on a given day because of the observance of a major religious holiday or related travel shall be excused and provided with the opportunity to make up, without unreasonable burden, any work that has been missed for this reason and shall not in any other way be penalized for the absence or rescheduled work. Students will remain responsible for all assigned work. Students should notify professors in writing at the beginning of the semester of religious observances that conflict with their classes. The Office of the Provost, in consultation with Campus Ministry and the Registrar, will publish, before classes begin for a given term, a list of major religious holidays likely to affect Georgetown students. The Provost and the Main Campus Executive Faculty encourage faculty to accommodate students whose bona fide religious observances in other ways impede normal participation in a course. Students who cannot be accommodated should discuss the matter with an advising dean.